Hit Movie

Shadowlands Tells Love Story of C.S. Lewis and Joy Gresham

Hit Movie

Shadowlands Tells Love Story of C.S. Lewis and Joy Gresham Hit Movie

Shadowlands Tells Love Story of C.S. Lewis and Joy Gresham

Hit Movie

Shadowlands Tells Love Story of C.S. Lewis and Joy Gresham [Published in The Pipe

Smoker’s Ephemeris, Winter-Spring 1994]

By Henry Zecher

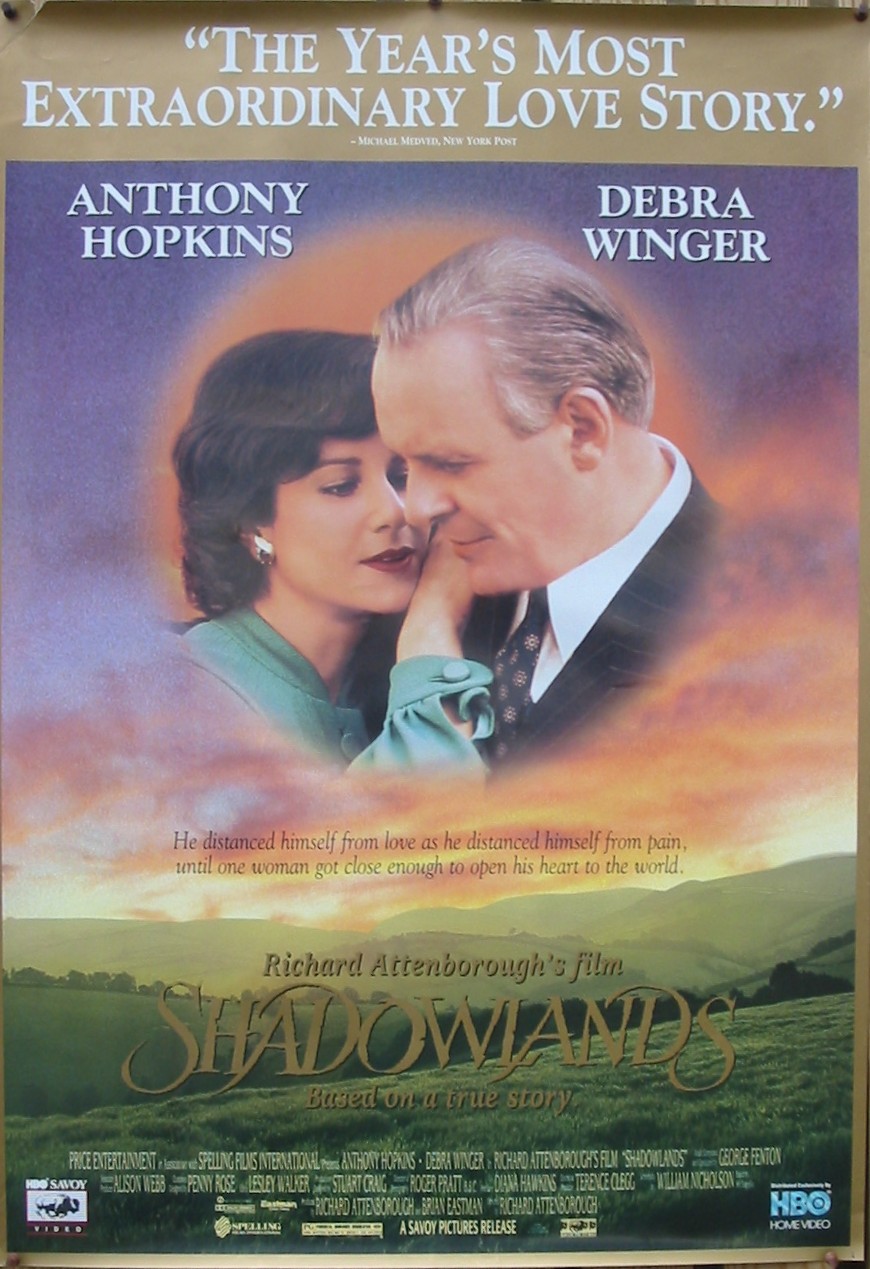

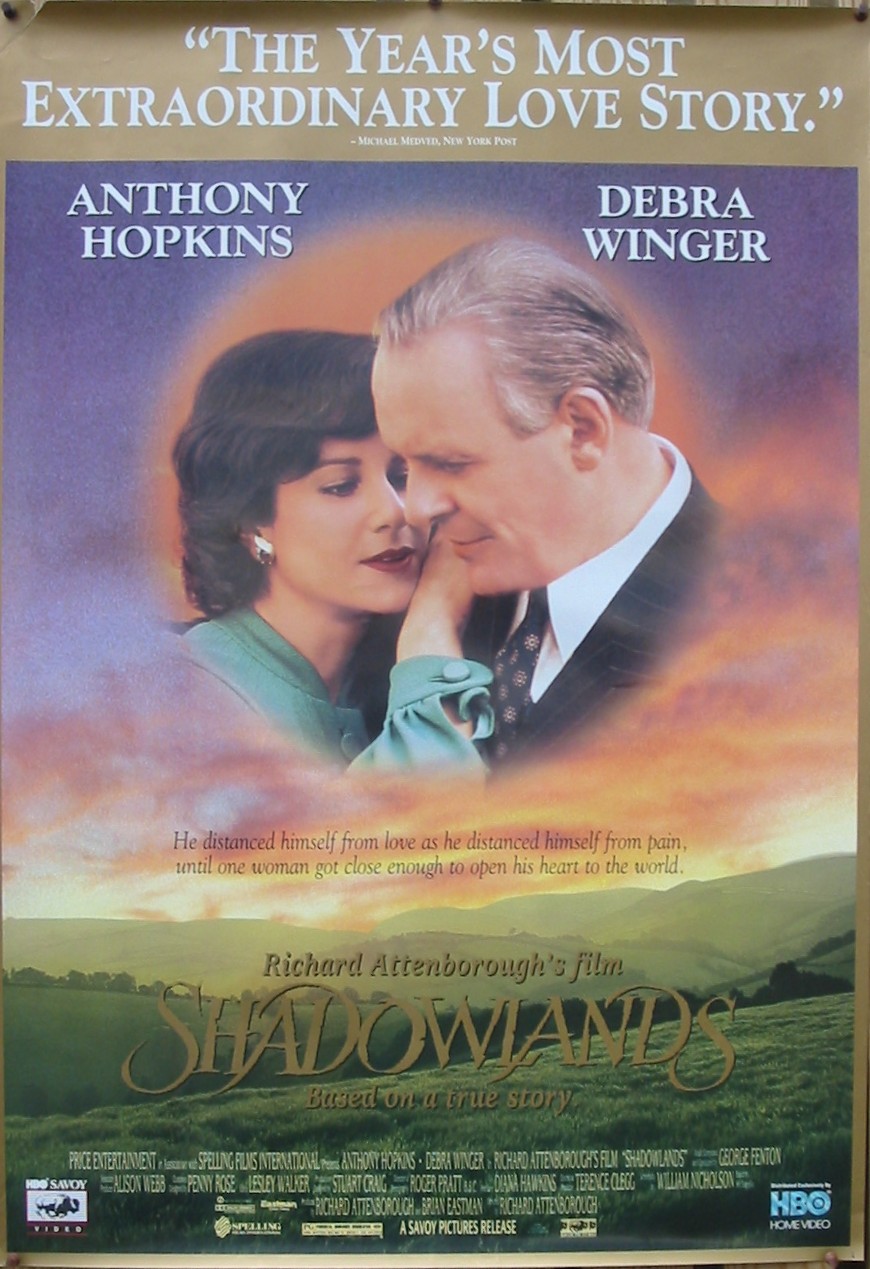

There is a new love story out on film this year, and it is taking

critics and viewers by storm. The film is Shadowlands, a remake of both

the 1985 BBC-TV film (starring Joss Ackland and Claire Bloom) and the popular

stage play, and it brings back to life both the world and the love story of

Joy Gresham and Clive Staples (C.S.) Lewis.

The movie's title comes from Lewis's oft-quoted reference to this life

as being mere shadows, or shadowlands, with the real life yet to come. But,

while we all know him as the great writer and amateur theologian, few know him

as a confirmed old bachelor-turned-lover. Yet it is in that endearing role

that he is now charming a new generation of viewers, this time in the

performance by Academy Award-winner Anthony Hopkins, who made the leap from

Hannibal Lector to C.S. Lewis with stunning affect. Joy Gresham is portrayed

by Debra Winger with the same kind of brilliance and directness the real

Gresham was known for. And Lewis's brother Warnie is portrayed by Edward

Hardwicke, perhaps better known to many for his role as Dr. Watson alongside

Jeremy Brett's Sherlock Holmes.

Shadowlands takes us back to England's Oxford University in the

year 1952. It was here that this international literary giant had reigned for

the past 12 years as the world's leading thinker, writer, and explainer of the

Christian faith. He was also a confirmed bachelor living with his brother,

Warren, in their rambling brick house, "the Kilns," at Headington, near

Oxford. When Joy arrived, "Jack," as his friends called him, found his world

begin to turn upside down.

C.S. Lewis was a tutor and lecturer in medieval and

renaissance literature at Oxford University, as well as being a well-known

critic and author, and a charming and witty man of letters. As a proclaimer of

the faith, he brought a clarity of thought and a breadth of imagination to

Christian apologetic that has never been equaled, before or since. For no

fewer than seven decades he has ruled the Christian literary world, and to this

day books are written, sermons preached, and doctrines upheld on the rock of

this man's thinking.

By all accounts a majestic speaker, he delivered his lectures on

campus with great gusto in a loud, deep, booming voice. He quoted medieval

texts in their original tongues, complete with translations, and it was

obvious he had read the books he taught from, enjoyed most of them, and wished

his pupils to enjoy them as well. And, Time Magazine noted, "His

lectures are an Oxford rarity: they are jampacked. It was his voice, rather

than his writings, that catapulted him into the public arena during the war

when Lewis made 29 religious broadcasts over the BBC to an average audience of

600,000 listeners. England was said to have rejected Christianity, he was

told, but he reasoned that England could hardly reject what it did not

understand. He also occasionally preached at Oxford's St. Mary's Church. Years

later, taped radio addresses on The Four Loves were broadcast in the

United States."

He began writing seriously in the 1930s. His great study of medieval

tradition, The Allegory of Love, placed him among the top literary

scholars of his time. He wrote a penetrating analysis of 16th century

literature which became Volume III of The Oxford History of English

Literature. He was even guilty of a small monograph on The Literary

Impact of the Authorized Version.

His Space Trilogy, appearing before the war, remained favorite

reading for many years, but it was The Screwtape Letters, published in

1941, that made him an international celebrity and became his most famous

book. It was uncommonly original in that it presented temptation and sin from

the devil's point of view, outlining his strategies and his objectives in a

series of Chesterfieldian letters from a chief tempter, Screwtape, to a novice

tempter, Wormwood, concerning Wormwood's handling of his "patient," a young

English gentleman who is never named. From Screwtape's perspective, this

patient backslid from his fallen state into religion, was rescued from the

grip of the Enemy by living among clever and worldly agnostics, regained his

faith, performed heroically during the London Blitz, and was then released

into eternity by a bomb. Screwtape has sold millions of copies over the

years and has become a classic in Christian literature.

Lewis tackled one of life's most perplexing questions in The

Problem of Pain, and made one of his most profound observations: "God

whispers to us in our pleasures, speaks in our conscience, but shouts in our

pains: it is his megaphone to rouse a deaf world." In Miracles, he

showed his Biblically-based beliefs by alternately upholding miracles as

exceptions to God's natural law and then shooting down such secular myths as

Joseph accepting the idea of a virgin birth because he didn't know where

babies come from. Lewis's point was that, while Joseph may not have known as

much as a modern gynecologist knows, he certainly knew that, when a man and a

woman come together, a baby usually follows.

His last great work, A Grief Observed, was a diary he kept of

his awful grief following Joy's death from the cancer in 1960.

But Lewis's greatest achievement, the magnum opus of his literary

career, was Mere Christianity, arising from his wartime BBC radio

broadcasts. This book is the clearest, simplest explanation of the Christian

faith ever written, and has influenced millions of readers, including Charles

Colson, former top aide to President Richard Nixon, later founder of Prison

Fellowship and now one of the world's great Christian intellects. Colson was

searching for God during the Watergate turmoil and read Mere Christianity.

Colson had contemplated God subjectively, at times of great emotion ~ whether

joy or fear ~ and figured that Lewis probably approached God the same way.

Then Colson opened the book "and found myself instead face-to-face with an

intellect so disciplined, so lucid, so relentlessly logical that I could only

be grateful I had never faced him in a court of law."

Far and away, however, Lewis charmed us most with his children's

stories, The Chronicles of Narnia, which showed how Jesus might have

appeared had He come to save another world different from our own. These,

Lewis said, were the type of stories he would have liked to read as a boy, and

they were, in the words of biographer Walter Hooper, "the unexpected creation

of his middle age, and seemed to be his greatest claim to immortality, setting

him high in that particular branch of literature in which few attain more than

a transitory or an esoteric fame."

The Chronicles also opened up a vast new audience for Lewis.

Where he had previously been read by, and corresponded with, adult readers all

over the world, including some of the leading intellectuals, he suddenly found

mail coming from the hands of children, most of them in Britain and America.

And this man, who felt it his calling to answer all correspondence personally,

took the time and trouble to write to each child as well. Never condescending,

Lewis regarded children as young adults and treated them in just that manner.

Thus, when one child asked him how he drew cats, he drew cats, admitting as he

did so that he was cheating by drawing them from the back, since the front is

much more difficult. When a child would find the connection between the Narnia

stories and the Gospels, Lewis always congratulated the child and added that

children usually saw the parallel while adults seldom did.

Lewis had already been recognized as the leading Christian spokesman

in the English-speaking world when his picture appeared on the September 8,

1947, cover of Time, with a full-length feature article within. "Lewis

(like T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden, et al.) is one of a growing band of heretics

among modern intellectuals: an intellectual who believes in God," the article

noted. It is not a mild and vague belief, for he accepts ‘all the articles of

the Christian faith..."

The "Apostle to the Skeptics," as Chad Walsh called him, was a most

entertaining and amusing fellow. He had a large red countryman's face and wore

shabby clothes; give him a brand new suit and it would look slept in the first

time he put it on. This gave him the appearance more of a prosperous butcher

than a university professor and widely-read author.

"I had never so much as seen a photograph of him," Sheldon Vanauken

wrote, "and in reading his books and letters I had vaguely pictured him as

slender, perhaps somewhat emaciated, and slightly stooped with a lean,

near-sighted face. What I met...was John Bull himself. Portly, jolly, a

wonderful grin, a big voice, a quizzical gaze ~ and no nonsense. He was as

simple and unaffected as a man could be, yet never was there a man who could

so swiftly cut through anything that even approached fuzzy thinking. Withal,

the most friendly, the most genial of companions."

He was never vain, wishing for the day when all his hair would fall

out so that he would not have to mess with it. In keeping copies of books,

including his own, he never went for first editions or handsomely bound

volumes. Any old paperback copy would do. When asked if he preferred to be

called "Doctor" or "Mister," he replied that he not only didn't care what

people called him, he usually never noticed.

Always concerned about those in need, he and Warnie regularly took

into the Kilns people who needed care and a place to stay, particularly during

the war. Deathly afraid of poverty, he nevertheless set up his Agape Fund from

his book royalties for channeling his money to help the poor and needy. One

woman in America, whom Lewis never met, lived the last three decades of her

life off a stipend Lewis established from those royalties.

Smoking among Christians is, even today in Europe, quite common and

not particularly frowned upon. In Lewis's day, even such prominent Christian

leaders as Dietrich Bonhoeffer in Germany and Peter Marshall in America

smoked. Lewis usually smoked a pipe, and photographs from his youth to his old

age show him with his pipes. He also smoked cigarettes; but, as he informed a

child in America, "Tell Nicky I don't smoke cigars."

Though certainly temperate in his conduct, he also enjoyed beer, wine

and other strong drinks. This, too, was and still is far more common among

European Christians than it is among Christians in America, where

fundamentalist readers often took him to task for smoking and drinking. Lewis

never tolerated such criticism, pointing out that Hinduism, not Christianity,

was the teatotal religion, that the Lord made wine and drank it, and that such

legalistic thinking was, as he told one correspondent, "so provincial (what I

believe you people call 'small town')."

Curiously, while defending temperate drinking, he was far less

defensive about smoking, telling one American lady correspondent in 1956,

"Smoking is much harder to justify. I'd like to give it up but I'd find this

v(ery) hard, i.e. I can abstain, but I can't concentrate on anything else

while abstaining ~ not smoking is a whole time job."

Lewis was one of those rare Christian figures who remained totally out

of religious controversy, and was accepted equally by Protestants and Roman

Catholics alike because he put forth straightforward, simple, "mere"

Christianity, the Christian beliefs common to most Christians at all times.

Though Anglican himself, he accepted into his fellowship all Christian faiths

who professed Jesus Christ as the, Son of God, and when it was time to part he

liked to remind his friends that,"Christians never say good-bye."

A man of scintillating wit, Lewis wrote to a correspondent: "Would you

believe it; an American school girl has been expelled from her school for

having in her possession a copy of my Screwtape. I asked my informant

whether it was a Communist school, or a Fundamentalist school, or an RC (Roman

Catholic) school, and got the shattering answer, 'No, it was a select

school.' That puts a chap in his place, doesn't it?"

To a child in America he wrote, "I never knew a guinea-pig that took

any notice of humans (they take plenty of one another). Of those small animals

I think hamsters are the most amusing–, and, to tell you the truth, I'm still

fond of mice. But the guinea-pigs go well with your learning German. If they

talked, I'm sure that is the language they'd speak."

Such humor in the Lewis household was by no means restricted to the

lord of the manor. One summer morning when Lewis was writing at his desk by

the open window, Snip (one of his wife's cats) took a great spring from

outside and shot in through the window. She landed with a great thump on top

of his desk, scattering papers in all directions, and skidded to a halt in his

lap. He looked down at her in amazement. She looked up at him in amazement.

"Perhaps," he told Walter Hooper, "my step-cat, having finished her

acrobatics, would like a saucer of milk in the kitchen." Hooper opened the

door for poor Snip and she walked slowly out, embarrassed, but with the best

grace she could manage.

The world of C.S. Lewis was one rich in academic achievement,

friendships and university traditions, but it was decidedly limited in its

scope, as the movie amply demonstrated. In 1952 that entire existence was

shattered by the arrival of an American woman named Joy Gresham and her sons,

Douglas and David. Joy was a Jew converted to Christianity through Lewis’

writings. She had been a communist and an agnostic, as well as an accomplished

poet. Now she was leaving behind her an alcoholic, violent and chronically

adulterous husband who now lived with and wished to marry another woman. A

divorce would soon be under way.

Although the real Joy Gresham had two sons, not one as this film

suggests, the rest of the story is pretty truthfully told: a growing

friendship, a civil marriage arranged solely for her to remain in England, and

the joke that, while his friends all thought they were not married and up to

sinful mischief, they were actually married and up to none. But their love

grew; and, after Joy was stricken with cancer and lay on her deathbed, Lewis

finally asked her to marry "this foolish, frightened old man who needs you

more than he can say, and who loves you even though he hardly knows how?" Joy

looked up at him from her deathbed and said, "OK, just this once."

What the movie does not relate is that Lewis had previously requested

a Christian ceremony but had been denied, since Joy was divorced and the

Anglican church forbade remarriage after divorce. The church could not make an

exception for Lewis simply because he was famous. With Joy on her deathbed,

however, the church felt mercy overruled traditional theology and, on March

21, 1957, they were married before God and the world.

Before long Joy enjoyed a remission of her cancer that appeared to be

miraculous: Lewis had prayed to God that her pain would be transferred to him,

and soon her cancer receded while he was stricken with osteoporosis. "I was

losing calcium just about as fast as Joy was gaining it," he wrote in

November, "a bargain (if it was one) for which I am very thankful."

Jack and Joy, he now just past 60, she in her early 40s, had three

truly blissful years together. They worked wonderfully together, stimulating

each other's minds. She encouraged and helped him write Till We Have Faces,

his finest work of fiction, The Four Loves, and Reflections on

the Psalms, his first theological work in eight years. He helped her with

Smoke on the Mountain, a treatment of the Ten Commandments that is

still in print.

She brought a woman's touch to a house that had not been decorated, or

even kept up, in 30 years of bachelor residence, and the Kilns became a scene

of domestic charm and gaiety. Warnie, in a position one would have thought

would make him jealous and resentful, as some of Lewis’s other friends were,

welcomed Joy, and loved her. Jack and Joy entertained friends and enjoyed a

mutual happiness that was both a surprise and delight to all who saw them.

"Jack and I are managing to be surprisingly happy considering the

circumstances," she wrote to Chad Walsh; "you'd think we were a honeymoon

couple in our early twenties, rather than our middle-aged selves." Without

question, these were the happiest and most contented years of Lewis's life. "I

never expected to have, in my sixties, the joy that passed me by in my

twenties," he said.

A most charming incident in the movie ~ and a true one ~ is when the

newlyweds traveled to a country inn. Upon arriving, Lewis was so nervous he

panicked on the telephone while ordering drinks from room service, and ordered

a drink he did not like. In a volume of Lewis' letters is this confession,

made to a correspondent in America: "I'm such a confirmed old bachelor that I

couldn't help feeling I was being rather naughty ('Staying with a woman at a

hotel!' Just like people in the newspapers!)"

After her death he would recall, "For those few years H. and I feasted

on love; every mode of it ~ solemn and merry, romantic and realistic,

sometimes as dramatic as a thunderstorm, sometimes as comfortable and

unemphatic as putting on your soft slippers. No cranny of heart or body

remained unsatisfied."

Lewis lived in a land far removed from the McCarthyism and blaring

horns of a barbaric America, in an era now known more for its golden oldies

than for its golden thought. Yet it was he who became the Christian faith's

most gallant knight warring against the forces of skepticism, agnosticism, and

unbelief. No thinker, no writer, no preacher has ever brought the complexities

of Christianity to a level of such simplicity and, most of all, logic, as this

Oxford don who was born before the century began and who died on the same day

~ November 22, 1963 ~ on which John F. Kennedy was shot. He became, and

remains to this day, the most popular spokesman for Christianity the world has

ever known.

It was at their first meeting that Vanauken "saw and heard, both at

table and at the semicircle by the fire in the common room as the port went

round, the Lewis who, in brilliance, in wit, and in incisiveness, could hold

his own with any man that ever lived."

|

C.S.

Lewis: "Then Aslan turned to them and said: '...you are ~ as you used to

call it in the Shadowlands ~ dead. The term is over: the holidays have

begun. The dream is ended: this is the morning...' "And for us this is the end of all the stories, and we can most truly say that they all lived happily ever after. But for them it was only the beginning of the real story. All their life in this world and all their adventures in Narnin had only been the cover and the title page: now at last they were beginning Chapter One of the Great Story which no one on earth has read: which goes on for ever: in which every chapter is better than the one before." |

© 2006 Henry Zecher

* * * * * * * * *

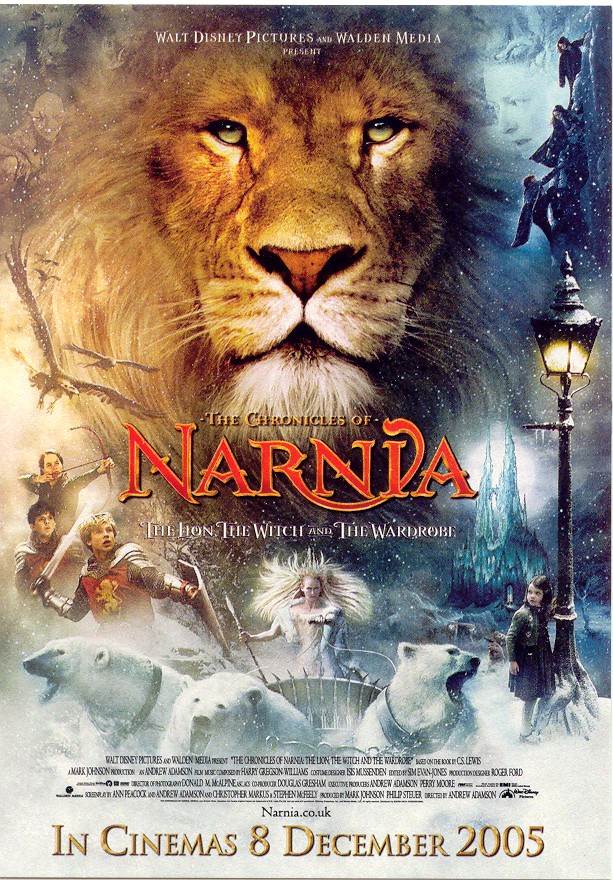

In 2005, Walt Disney Pictures, with distribution by Buena Vista Pictures

Distribution and production by the C.S. Lewis Company and Walden Media,

released The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe,

to world-wide acclaim. Filmed on location in New Zealand, the Czech Republic,

and London, England, and directed by Andrew Adamson (Shrek and Shrek

2), the film opened on December 9, and grossed $247,777,824 in its first

five weeks.

This review by marthahashagen (movies profile) December 9, 2005, was

the most fun ~

My dear Wormwood:

How did this movie get by us and into theatres? I thought we'd been

relieved of C.S. Lewis years ago! This story has the mark of The Enemy all

over it and is to be taken very, very seriously!

All we can do is remind the patient as he watches this movie that

virtues such as courage, and valor, and altruism are only fit for children and

children's movies. Mention to the patient that in the "Real World" (his own

euphemism for greed and lust and laziness and all sorts of transgressions

against The Enemy) such virtue is laughable, even "cute", and very, very

childish!

We're going to have a fight on our hands with this one. It doesn't

help that the acting was excellent, the children were great and the animation

was superior. Where did they get that lion? Oh, well ~ we can't win them all.

After he sees the film, remind the patient of his last income tax return and

he'll be ours once again.

Yours affectionately,

Screwtape

[Color print of C.S. Lewis provided by Historical Reproductions ~

www.historicprints.com ]

![]()